Worcester and the Nipmucs

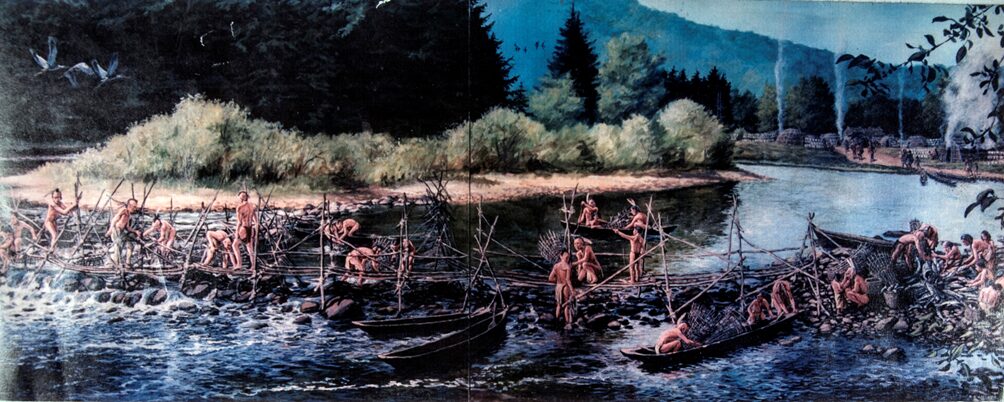

Painting by David R. Wagner. Used by permission.

Before Europeans came to America, the area now known as central Massachusetts was called Nipnet, or “the freshwater pond place.” “Nipmuc” is the native name for the original people of this land. At that time, they subsisted by planting food, hunting and gathering. Nipmuc women were the keepers of cultural norms by passing them from one generation to the next. They were also responsible for farming and feeding their families. The traditions and lifeways of matrilineal systems of leadership and stewardship, connected to processes of seasonal planting and harvesting continue to this day.

It is believed that the Nipmuc population dwindled even before colonization due to contact with European traders and fishermen, which led to disease for which they had no immunity.The first documented contact between the Nipmucs and Europeans was in 1630, when the Nipmucs provided corn to starving colonists of Boston.

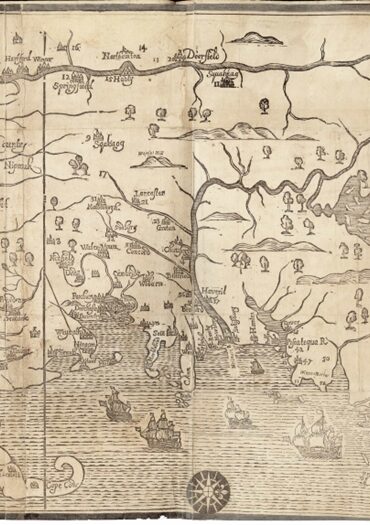

Land in the Quinsigamond area (on the eastern side of modern day Worcester) was considered fertile by early European settlers in Eastern Massachusetts. Colonists who came to this area in the early 1600’s were encouraged by the colonial authorities to wage unlimited war on the Nipmuc people. They destroyed native villages by burning the homes, trampling on the gardens, and killing women and children. After military conquest by the colonists in the 1660’s, land grants were given to a church in Malden, as well as to powerful English settlers in appreciation for these violent acts. The colonists engaged in a concerted effort to convert Nipmucs to Christianity, often by force or coercion. Early settlers documented villages of Christian converts (“praying towns”) in the immediate Quinsigamond area, including Packachaog (on the southeastern side of modern day Worcester), Hassanamesit (now Grafton), and Weshakim (now Sterling).An additional hamlet was called Tataesset (modern day Cascade Park and Asnebumskit Hill), and there was another village on what became known as Wigwam Hill on the western side of Lake Quinsigamond.

Metacom, a chief (sachem) of the Wampanoag in Southeastern Massachusetts, abandoned his father’s alliance with the English after several violations by settlers. In 1675, battle lines were drawn, with some natives siding with the colonists and others, including many Nipmucs, joining Metacom (who had taken the English Name, “Philip”).The “King Philip War” became the deadliest war in colonial American history, and the impact on the Native American population cannot be overstated.

After the war, few natives returned to Quinsigamond. English settlers took advantage of the disruption and acquired the land from the Nipmucs, paying with only trucking cloth and corn. A committee of English settlers formed and, within a few years, they agreed to rename the town “Worcester.” The area of North Pond, where UUCW now sits, was granted to George Danson, a baker of Boston. Danson soon built a mill here. In 1828, North Pond was dammed to increase the amount of water for use by the Blackstone Canal, creating “Indian Lake.”

There are nearly 600 members of the Nipmuc tribe living in Massachusetts today.The four-and-a-half acre Hassanamisco Reservation and Cisco Homestead in Grafton, Massachusetts have been continuously controlled by the Nipmuc people since the mid-1600’s.Their reservation and homestead were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

As an 8th Principle Congregation, UUCW is committed to honoring the history of the Nipmuc people and supporting the Nipmuc community and the interests of indigenous people in Central Massachusetts. We encourage you to learn more about Nipmuc history and heritage.

Resources

Nipmuc Indian Development Corporation

Nipmuc Tribal Council of Chaubunagungamaug

No Loose Braids is a Nipmuc-led organization focused on continuing and reviving Eastern Woodlands traditions and cultural practices.

UUMass Action is a statewide action network with a mission to organize and mobilize the 20,000 Unitarian Universalists and 142 congregations in Massachusetts to confront oppression.

Sources

Grenier, John. The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607 – 1814. 5, 10 New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Quoted in An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Beacon Press, Boston 2014

Gould, D. Rae; Herbster, Holly; Pezzarossi, Heather Law; Mrozowski, Stephen A. (2020). Historical Archaeology and Indigenous Collaboration: Discovering Histories That Have Futures. University Press of Florida..

Lincoln, William; Hersey, Charles. History of Worcester, Massachusetts, from 1836 to 1861. Accesed from https://archive.org/details/historyofworcest00inlinc.

www.worcesterma.gov/city-parks/indian-lake-beach

City of Worcester – Indian Lake Beach